Fable one: It was in the early 2000s. The newly established Gafeschian Contemporary Art Museum in Yerevan (Armenia) had just opened its doors in the renovated regional-modernist style architectural complex called Cascade. This iconic structure located in the most beneficiary central spots of the town had been abandoned for more than a decade and had been brought back to life in that most pivotal period in the history of independent Armenia. The country was starting to revive from a decade of economic crises and to establish communication with the outer world after 80 years of isolation during the Soviet period. The spirit of innovation and freedom was everywhere. I happened to be among the generation of architecture students in those years who were the first disturbers of architectural traditions and the first rebels against old conservative thinking and design methods in architecture. It was a tough battle against a whole army of traditionalist ultra right-wing architectural dinosaurs survived from the old Soviet times. The battle was a typical ideological war between generations, except that the older generation was fighting for traditional values because, right or wrong, it was their deep and honest conviction that architecture is about rationality and optimal solution, rather than a circus of shapes and forms. Whereas the younger generation on the other side of the barricades was fighting for the idea of ‘modernisation for the sake of modernisation’, not least because it was simply cool to do so. The information about new tendencies in world architecture was just starting to soak in. It was intoxicating, enchanting simply to look at the images of Gehry, Hadid and Libeskind architecture. No one back in those times would really have looked deeper into the technical, functional or conceptual aspects of what was hidden behind those fascinating shapes. It just looked so cool, so new! So novel and free!…And that’s what really mattered.

On one of those days I happened to go up the escalator of the Gafeschian museum, passing platforms exhibiting pieces of pretty bizarre contemporary art, when I noticed something at the junction of the wall and the ceiling. It was a big metal truss structure protruding from the wall covered in places with heaps of an unknown constructional compound. This messy structure had something very artistic in its appearance, even something deeply conceptual. Was it the overall intoxicating atmosphere of novelty and bold creativity that illuminated this unusual piece with an air of artistic mystery? Whatever it was it certainly made me burst: “How cool!” Enthusiastically I immediately took some shots of this wonderful ‘art work’ and returned back home. After uploading the pictures into the computer I no less enthusiastically started studying this piece trying to discern traces of a highly sophisticated concept which the architect or the artist would had encoded somewhere in those blended folds of iron and concrete. After musing for some time, however, I had to come to the conclusion that there was no particular meaning in that structure, except of it being a metal truss that for some unknown engineering purposes was left uncovered in that otherwise perfectly refurbished interior.

What happened to me is a common story that happens to people while encountering with contemporary art. Sometimes it is confusing to identify the thin line between a true concept and banality. For me this intellectual incident was an interesting experience which helped me to understand how much my generation was sunk into the ubiquitous ‘coolness’ mania. The young architecture students were prancing around exhibiting the most extravagant colored hair looks, D.I.Y. clothes and accessories, some of which were admittedly quite funny and creative. Here and then would also emerge some avant-garde gangs of architecture students whose professional advancement was pretty much measured by their ability to spell correctly the names of Zaha Hadid and Franck Gehry. Not least by their collections of contemporary architecture photo galleries downloaded from the internet.

This rage for innovation is actually well understandable and could be even considered as a dialectic development of the history. By the end of a historical period there is usually a large amount of energy (or information) accumulated which once reaching its critical mass seeks a breakout to transform itself into a new matter (or knowledge). It is usually at that very time that rebels or innovators arrive to explode and subvert the old system. They bring up deconstruction and build the new system with the very energy of that deconstruction, using the ashes of the exploded system as construction material and the know-how of their own times as their tools. This is exactly what was happening among the young generation of architects in Armenia and many other Post-Soviet countries in the early 2000s. Except that deconstruction and would-be-modernization were then ends to themselves and not underpinned neither by the experience of the past, nor by any new ideology.

To me this very noble aspiration for modernization or a new modernity was clearly doomed to failure. The reason for this was what I call the ‘Syndrome of Provincialism’, going hand to hand with some sort of ‘Syndrome of Coolness’. The Provincialism Syndrome is notoriously orientated towards quick results, the superficiality of which usually is masked under the superficial gloss and glittering. It is hardly interested in concepts hidden deep beneath the rhetoric of some stylistic maneuvers. After all it is much simpler to monkey a look than to sweat over the complex rules conditioning a style.

Provincialism hence goes for success rather than process. Provincial architects have a great ability for absorbing visual information. They digest visually tones of architectural designs and then cleave it into some simple elements which they later assemble as Legos into new architectural designs. In this process cleaved elements lose their original, initial meanings and appear in the new design as naively quoted symbols, rather than as functional or tectonic elements. This ‘cleaved-assembled’ approach to architecture is an omnipresent practice which has nothing to do with the elaborate process of critical assimilation of the past experience or prototypes.

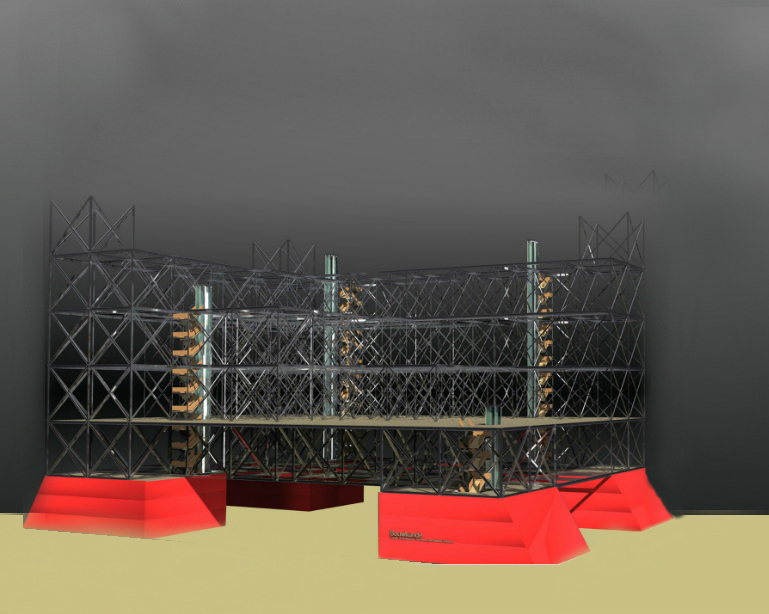

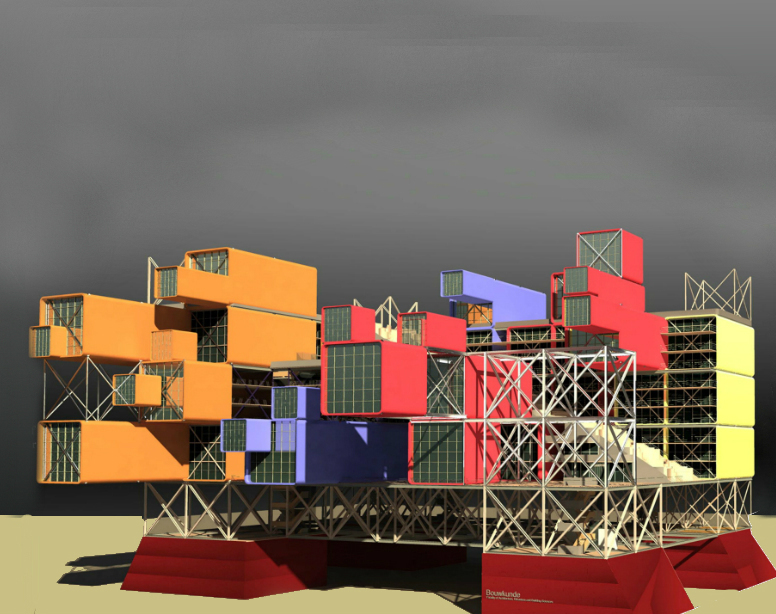

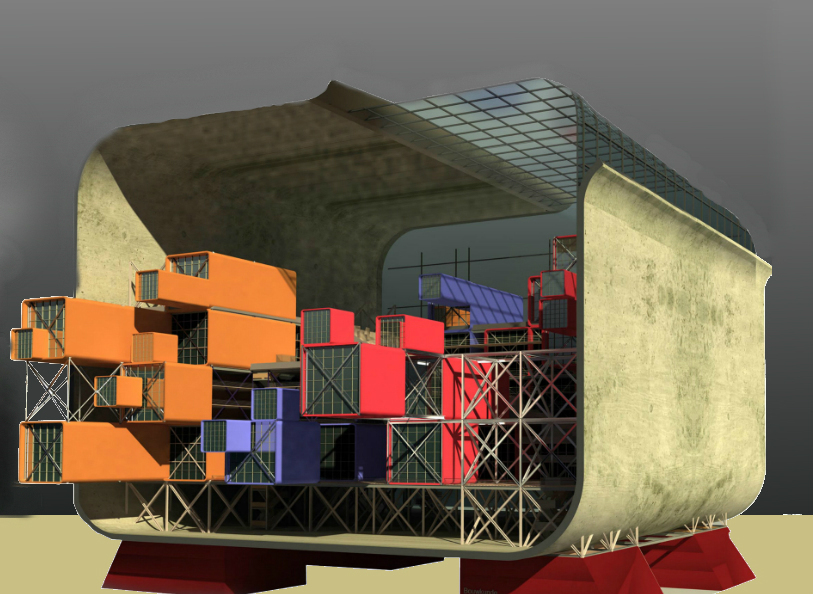

Fable two: In 2008 I decided to participate in an international architectural competition of a new building for the architectural faculty of the Delft technical university, called Bowukunde. It was a challenging task to which I had to respond through a very contemporary architectural idiom. Hence I decided to scan examples of contemporary architecture available online in order to derive its ‘spirit’ and perhaps synthesize the methods on which it operates. It took me some 15 minutes to browse several hundred projects in one of the online architecture websites (God bless the Web!) and to extract several structural principles or motifs which were appearing more or less similarly in many projects. What was left to do was to assemble those elements into a new structural composition of my own and adapt it for the brief of the competition. In a sec I was on the track of thousands of young or older architects worldwide and particularly those from the Post-Soviet territory who would surf internet on daily bases to produce later more and more replicas of the iconic looks of that mainstream avant-garde architecture. Then when the competition projects were presented online (several hundred entries!) I found the very same motifs I used in my project present in at least every second project.

We are living in an era when global culture is predominantly defined by mass media and a constant reproduction of looks, call it fashion looks or architectural looks. The term ‘look’ itself came to replace the term ‘style’, which itself already was putting in danger the possibility of critical and independent thinking. With the advent of the term ‘look’ things became even more superficial. To practice a style one was supposed at least to have certain knowledge of the principles and regularities conditioning the language of that style. Whereas a look gives you a ready-made recipe how to synthesize one single stylish case.

Architects nowadays feed themselves or, as they might prefer to put it, ‘inspire’ themselves from each others’ works images of which are spread abundantly all over the world. In this abundance of visual information what becomes of primary importance is the look of the building. It is the look and not the underpinning meanings or requirements constituting that look that are being copied. The ‘cool looking’ effect becomes an end in itself. It seems to me that the whole architectural society is developing Syndrome of Provincialism against some imaginary standard of a progressive, avant-garde architecture. Except that in this rage for more and more architectural ‘coolness’ architects stop discerning deliberately designed concepts from impostors.